- All

- Accounting & CPA

- Advertising

- Agriculture

- Alphabets

- Animal & Pet

- Apparel & Fashion

- Arts

- Attorney & Law Firm

- Auto & Transportation

- Beauty

- Childcare

- Cleaning

- Communication & Media

- Community & Foundation

Extensive research on autism has been done in the past, more is being conducted even as this is written, and untold numbers of studies and papers will be released in the future as we seek to understand ever more about this complicated condition. Even with all of that, there is so much that we don’t yet know about the autism spectrum.

Autism is one of the fastest growing disorders, with the World Health Organization stating that one in every 160 children has an autism spectrum disorder. These disorders vary widely in the amount in which they impact the child diagnosed; while some can grow up to live independent lives, others may need care and extra support throughout their lifetime.

Those who have autism are said to fall on a "spectrum." As can be gathered from the term itself, there is a spectrum of disorders, aspects, signs and symptoms that might be

istock.com/GeorgeManga

expected or felt; there is no guarantee that any one child with autism will see the same results as any other child with autism. Some children with autism may not even be identifiable as such to the casual observer; others very definitely display as different from the "norm."

Regardless of where a child falls on the spectrum, each one needs to be given attention, support, and encouragement in the way that is most effective for him or her. This, in turn, impacts all of those who interact with the autistic child, especially as they have more of a part to play. For parents and caregivers, teachers, and schools and other institutions, finding the best way to support the child is of continuing importance.

With such a wide field to address, it necessitates the development of an equally wide variety of ways for addressing and assisting those with autism.

Ever more ways are being developed to address the variety of autism spectrum disorders; psychosocial intervention methods include things such as behavioral therapy and programs for the parents and caregivers which train them in ways to assist their affected children.

Across the globe, there continues to be a stigma attached to autism and those who deal with it. The more research and understanding of the condition, the more people will accept and support those who are affected — at least, that’s the hope.

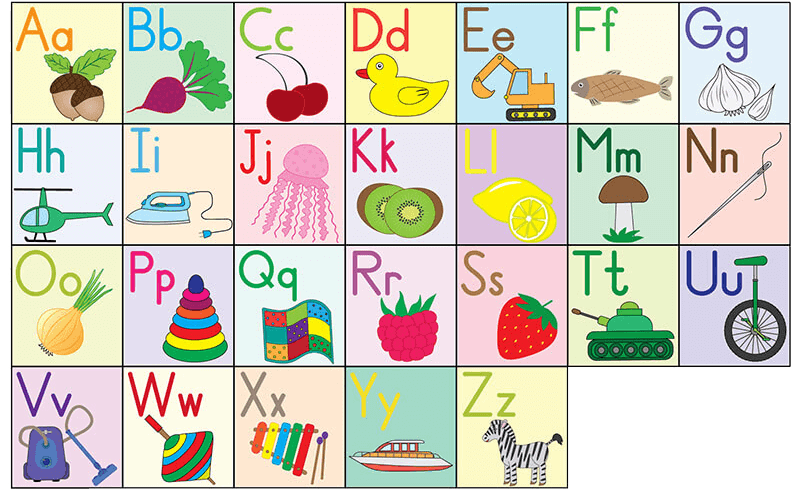

One key aspect of research, however, is in the ability of visual design to stimulate a response in children with autism. This is important not only in assisting in the education of the children, but also in helping them to develop life skills that will be useful to them in the future. Teachers and parents especially may be interested in the research on visual design, as it can positively impact how the child learns.

Visual design is important for any child — or any adult, for that matter. It has a great deal to do with effective communication and learning. But certain aspects may need extra attention when it comes to visual design for autistic children when exploring creative visual design.

Why is that?

Any child, especially a young student, will delight in a variation of colors, sizes, fonts, textures, and patterns in their reading, learning, and play material. There’s a reason why toys and books, especially for younger children, are a riot of primary colors: colors attract the child, engage their interest, and then assist to keep it long enough to learn or complete a task.

The psychology of color is a vital part of visual design — we'll go into that in a later section.

But visual design is more than just the color palette. The other elements used, graphics, images, spacing, fonts and typefaces all play into the message communicated by visual design. Especially before a child learns to read, or to read fluently, the visual aspect is especially important.

For a child with autism, the visuals may never stop being the primary way that they learn and communicate. Though they may be limited with traditional methods of learning and communication when compared to those not on the spectrum, that doesn't mean that there’s no way to reach them. Modern teaching methods focus not solely on the traditional, but on being flexible and adapting to the needs of each learner.

Let's talk about one important method.

On the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) website, an article on functional augmentative and alternative communication for students with autism suggests that those on the autistic spectrum are prime candidates for augmentative and alternative communication methods, either to enable them to communicate more fully or to act as their primary method of communication. Among the alternative methods suggested are manual signs, voice output aids, and graphic symbols.

This last is particularly interesting, in the field of the effect of visual design on children with autism.

If graphic symbols are a possible way not only to communicate more effectively with children with autism, but to allow them to communicate in return, clearly the visual aspect deserves more investigation.

There is, however, a note of caution when considering designing for children with autism, regardless of how good your intentions are.

What do you need to keep in mind?

It's important to take into consideration the difference in views that are held on the autism spectrum, and those who have one of the disorders.

Some view autism and other disorders not as disabilities but as conditions that collectively fall under the term "neurodiversity." Though this is defined in different ways depending on what research material you read and who you talk to, author John Elder Robison, who writes the blog My Life With Autism for Psychology Today, defines

istock.com/Kuliperko

neurodiversity as “the idea that neurological differences like autism and and ADHD are the result of normal, natural variation in the human genome." Though this viewpoint is not accepted by everyone, Robison states that it is increasingly supported by research and science.

This changes how design for children with autism is presented — ie., sensitivity is important, and rather than focusing on autism being something that is innately wrong or negative because of its differences from the norm, a designer should rather focus on assisting and supporting those who are neurodiverse, whatever the specifics of their disorders. Again, for teachers and schools and others who support parents and caregivers, it's important to not only keep up with the research, but take into account the individual views of parents and families.

Those who identify as neurodiverse often have a very different perception of what they see. This includes not only specific aspects of visual design, such as color and shape visuals, but also the emotion and message that is communicated by the design. Butterfly icons and logos may be perceived differently by autistic children as compared to kids who do not have autism.

Let's take color as an example.

Most articles that discuss visual design and the importance of being choosy with your color palette will probably mention the psychology of color. Certain colors tend to elicit certain emotions or responses.

Books such as Color Psychology and Color Therapy by Faber Birren have entire sections on the influence of color choice on emotional reactions, those with psychological differences, and our associations and memories.

Full Fabric, in a blog article on designing visual learning resources for neurodiverse students, states,

Colour can add meaning, clarity and dimension to visual materials; it can bring order and truth to the visual learner.

This is no less true of using color in visual designs for children with autism. But it's important to note that certain color choices may elicit “nontraditional” reactions from autistic children.

A study by Marine Grandgeorge and Nobuo Masataka investigated the color preferences of a group of boys on the autism spectrum, as compared to a group of non-autistic boys of the same age group. They found that the boys with autism were significantly less likely to prefer the color yellow, thought to be due to the "hyper-sensation characteristic" of autism, causing the boys on the spectrum to perceive the bright color as a sensory overload.

Since those on the spectrum tend to be easily susceptible to sensory stimuli, the color yellow was just too much to process.

When considering visual design for autistic children, this would be a trigger that should be avoided as much as possible.

According to the Grandgeorge Masataka study, the boys in their group were more likely to prefer greens and browns. The Sensory Differences: Online Training Module also adds blues to the preference. and the Full Fabric article states,

When it comes to colours, neurodivergent students tend to prefer muted and pastel hues and neutral tones.

Just like with the traditionally accepted psychology of color, choosing colors for autistic learners can work as a sort of shorthand to trigger the desired emotion. The book Colour Coding For Learners With Autism discusses how color coding can help a designer to create meaning for an autistic learner, helping to assist with communication and minimize anxiety.

While yellow is often considered to have a friendly, warm feeling to it, it is too much of a sensory stimulation for autistic students. Muted, neutral, and calm colors, however, can trigger peaceful and positive emotions, helping the child to avoid the overstimulation that comes from overly bright color palettes graphic.

Though color plays a very important role in stimulating cognition and eliciting emotions from a learner, it shouldn't be the only way of communicating visually, simply because there are some colors that transmit the wrong message, depending on the viewer.

These are important facts to remember in visual design, and can affect not only a designer, but a teacher, for instance, who is setting up a classroom. In order to appeal to neurodiverse students and give them a comfortable, encouraging environment in which to learn, the choice of colors may be adapted. The same goes for parents with neurodiverse children, in choosing the look of the child's room, toys, and other things inside the house. Though this research may seem limited in scope at first glance, color is everywhere — so the possibilities for employing it effectively in various aspects of life are endless.

Author Maureen Bennie, founder of the Autism Awareness Centre, writes, “People on the autism spectrum tend to learn best using visual supports rather than through auditory input. Seeing it, rather than saying it, helps the person retain and process information.”

A visual support, in the context of visual design, would be any image, picture, illustration, or text.

Images or photos that are simple, not overly colorful, and in which the main focus is easy to detect work best for helping autistic children to think and to learn.

Visuals can help an autistic child to "see" a thought in a way that isn’t possible from just hearing or reading about it. Picture, as an example, a calendar. Some people may prefer to have it in list format, reading down the page to find their schedule; others prefer the month laid out in a weekly format, with a large box for each day indicating the progression of the month. Different visuals are more effective for different people.

Much like a monthly calendar, a mostly-visual layout, with little to no text, may work best for helping a child with autism to learn, process, and retain the information they take in.

Simple images and icon designs for education also serve to both anchor the text they accompany, and break it up into smaller pieces that are easier to process and retain. Even if the child does not fully understand the image as it is presented, the visual will still help them to form memories and keep the information in mind, serving as a sort of memory trigger.

Too many images, or images which are too complicated and which the child cannot find the focus on, will serve to confuse the issue. And superimposing the accompanying text over the image can render both components more difficult to understand.

But simple images, used in the right place and the right time, can greatly assist a learner with autism, which in turn will help them to grow in confidence.

A flexible, adaptable teacher can employ different visuals in their curriculum, appealing to neurodiverse students.

Simple design may be viewed as having only a few key elements: perhaps a basic image, a few colors, minimal text. Typically, simple visuals work the best for stimulating cognition and positive emotional response among autistic children.

However, this interesting study on the different visual preference patterns in response to social stimuli brought to light some other aspects of designing for autism. The study's results state, "Eye-tracking studies in young children

istock.com/EnginKorkmaz

with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have shown a visual attention preference for geometric patterns when viewing paired dynamic social images (DSIs) and dynamic geometric images (DGIs). So, while keeping the design simple works the best for helping the autistic learner to retain information, simple geometric patterns can be eye catching and stimulate the interest of the child.

Coupled with the research on the impact of colors and visuals, this gives designers, teachers, and parents a wide palette to work with in choosing the environment for an autistic child.

Since the autism spectrum covers such a wide variety of needs and deficits, some children with autism will benefit more from learning orally, or being verbally instructed, while others will respond more readily and get more benefit from visual teaching methods.

Visual teaching methods have been increasingly focused on for a number of reasons. Along with the increase in autism, dyslexia, and other disorders that impact how a child learns effectively, there is simply a difference in how individuals process and retain information — how they learn. The traditional method, used for so long, of reading a text and testing the retention of knowledge only works for a certain percentage of students, not for everyone.

istock.com/Nosyrevy

Children with autism may rely on being taught via visuals, which is part of why visual designs that actually stimulate the child to deeper cognitive function and evoke appropriate emotion and response are so important.

Taking into account aspects such as typography, simplicity of the images used, and color psychology specifically for children on the autism spectrum can go a long way to helping a child to benefit emotionally and cognitively from visual teaching methods.

For designers, teachers, parents, caregivers, and peers, assisting and supporting children with autism should be a primary concern. While living with an autism spectrum disorder, or someone who has one, isn’t always easy, there certainly are ways and methods that can help.

istock.com/bubaone

And there's a lot to be grateful for. Author John Elder Robison, quoted earlier, wrote a blog discussing the end result of neurodiversity — far from being a depressing story of endless struggle, he highlights the positive aspects that he himself sees, firsthand, as someone on the autism spectrum.

Even though the root causes of the issues that some autistic children may have are poorly understood, Robison writes in this article,

There is no question that neurodiverse people have brought many great things to human society.

Though research is still ongoing and there is still much to be learned about the great variety found on the autism spectrum, there is always reason for positivity. If certain methods such as intelligent and focused visual design can help to stimulate and uplift children with autism, rest assured that there will always be those who are willing to think outside the box and experiment until they find what works.